"Painting Time" was written in 2019 as a requirement for completing my Master of Fine Arts degree at the NY Academy of Art.

Painting Time

Time’s Up

I think best while standing in the shower. A glass-walled stall shower is most useful. The steamed-up glass makes for a good writing surface if I want to jot an idea or do some math. When I was a practicing scientist I would work out the day’s experiments before heading to the lab. I could consider the question I wanted to answer and the controls I would need to reduce the variables to one. The shower is where my breakthrough ideas invariably ma- terialized. Problems are solved there. There are no distractions as there are when driving or walking the dog. Just a downpour of hot water with its white noise on the tile floor. Sometimes, of course, I think about more mundane things. What to make for dinner, where to go for vacation, sex, etc. But often, I think about my art. What to paint, for instance, and how to paint it. What studies should I do? Would the subject be better rendered as a drawing or a print?

Paintings can be about many things. Narrative, composition, light, space, color, reality, and fantasy are a some of these. Lately, my ideas on sub- ject matter have been revolving around time. This train of thought arose from two events. One was reading Sapiens, A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari. This book begins with the creation of the universe and takes us to the present day while looking along the way at the biology and sociology of the development of our species and culture(s). It suggests that we are at a significant turning point in history.

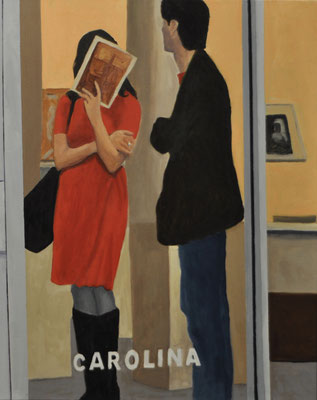

The other was the rediscovery of some photographs that I took about ten years ago. While standing across the street from an art gallery in Chelsea, I saw a couple through the gallery window. He was looking at work on the wall and she was gazing at a catalog when, suddenly, she looked up and saw me with my camera pointed in their direction. She immediately covered her face with the booklet. Why did she hide? I have no idea but, I captured this act in several photographs, thus collecting a sequence of moments. When I found these again years later, I thought they would make an interesting paint- ing - paintings, actually - and that led me to look at other instances where, having captured a moment, I am intrigued by what might be happening in the next moment. I think of Sherlock Holmes admonition to Dr. Watson,

Gotcha! (oil on canvas, 72x30”, 2017)

“You see, but you do not observe.” (Doyle) Our senses are continually exposed to an astronomical number of stimuli and most of them are ignored by our consciousness though not necessarily discarded from our memory.

About Time

Time and the universe began with the Big Bang, about 13 billion years ago. There was no time before then; there was no need for any. Matter, en- ergy, and space also came into being and not long afterwards the matter and energy formed atoms and these, in turn, formed molecules. Fast forward to about 3.8 billion years ago on Earth.

Life began and with life came problems. Early life, microscopic beings and, later, plants, got energy from the sun. When the first animals evolved, they ate the plants. Later came animals that ate other animals. So the problem for all organisms was to find enough energy sources to maintain existence long enough to reproduce without becoming the energy source for something else. Reproduction was necessary because nothing lives forever. There are thermodynamic reasons for this but that fact will suffice for our purposes here. Nothing lives forever.

The first humans, genus Homo, evolved about 2.5 million years ago; modern humans, Homo sapiens, about 200,000 years ago. They were hunter- gatherers. Agriculture started only 12,000 years ago. The first kingdoms and organized religions arose around 5000 years ago; Christianity, 2000 years ago. Then the Middle Ages. After all this time, they don’t seem to be in the middle of anything at all, do they? They were just the prelude to the Age of Enlightenment, the Scientific Revolution and the Industrial Revolution. Of course, the struggle for existence has always been with us; it’s part of living for all of life. Our ingenuity is the tool we have to both wage and resist this struggle.

Now, in the current modern times, we seem to be scarcely more evolved than we were 5000 years ago. We are still divided into groups: families, clans, nations, that are constantly struggling to dominate one another. At the same time, they must fend off domination. This need to dominate seems to be built into our biology. It is ironic that for all the differences that one calls out between whatever “Us” one might choose to distinguish from whatever one’s choice of “Them” might be, nothing of significance is actually different. We are all descendants of a common ancestor; that is, we are all cousins. And we all want and need essentially the same things: to have our logistical needs met (food, shelter, etc.), to have a way to contribute to the common good, and to have a loved one or ones with whom to breed. You would think that if we’re so smart, we could provide these. There are certainly enough resources to go around. But “Smart” is not “Enlightened.” Enlightenment is something you come to; you can’t just read about it and be so. Getting to Enlightenment is a journey. When you arrive you will know there is a Self that is common to all. Not a “yourself” or “myself,” just a Self. Only our stories are different, the tales we tell each other to describe “who” we are are, or what we think we are at the moment. And, as for a state of existence, that there is just the Moment. This is it. The past has happened and is over, the future is to come and it can be anything. At any instant, there is only Now. Yet, our customs, our education systems, our biology, all keep us operating in a state of, what? “Endarkenment?” We are cynical, we are afraid. And our political systems keep us that way for the benefit of their own survival. This is illustrated in what I think is the most important book of the last century, George Orwell’s 1984. In the Orwellian dystopia there is no objective truth, facts are what the party says they are; Big Brother is always watching (Alexa?); the country is constantly at war, and hate rallies are a daily occurrence. “Who controls the past controls the future, who controls the present controls the past.” (Orwell) When the current state of affairs looks like this, it’s time to do something about it. (That actually is a constant in human affairs and will be until we get politics right.) But it’s not an easy job. Another 1984 slogan is, “Ignorance is Strength” and there’s an abundance of ignorance on hand. This is not an accident. Our American education system is not designed to produce sophisticated, thoughtful, inquisitive citizens; just complacent ones.

So what can a socially conscious artist to do in the current political environment? Produce work that reflects and reveals the plight of humans and the state of society so the viewer sees life and the world from a fresh perspective. Celebrate our relationship to our natural environment and the diversity of our species and all of the other species that share our ecosphere, the Earth. Expose the forces that foster divisiveness and conflict among people and the destruction of habitat. Promote cooperation over domination so that we rise above Darwinian destiny and earn the benefits of a true Civilization.

My Time

My time and universe began in Ann Arbor, Michigan on a snowy November night in 1946 when I was evicted from a cozy, warm, quiet womb. Birth is what I identify as the worst moment in life. Before birth there is no hunger, no thirst, no noise, no struggle against gravity. It’s never too hot or too cold, always just right. Eventually, you start to feel a little cramped and feel the need to move your muscles. Then out you pop and it’s awful. Noisy, cold, smelly. You have to breathe on your own and myriad things make you uncomfortable. From then on, life is nothing but problems until the very end when your problems evaporate and you become a memory. No wonder everyone, consciously or not, wants to return to the womb. (And no wonder the female nude is universally admired; the male, not so much.) Like everyone, I’ve spent my life facing and solving problems. The mundane ones concern the basics of survival. The interesting ones have been the creative challenges: drug development, preventing HIV transmission, designing research laboratories, raising children, playing the piano. And, of course, painting.

Time is an element in all art. A representational painting depicts people, a place, or a thing at a moment in time. And the time is always in the past (even if the image is “the future”). A portrait represents time I spent with the sitter. A landscape reminds me of a place I’ve been. A still life is time I’ve spent fixated on some object. And stepping back a level, each painting is a record of the time I spent creating it; my sequence of brushstrokes is a diary of sorts. In contrast, abstract art is always about the present; the immediate reaction that the piece provokes in the viewer. It can be bold strokes of great fury (think de Kooning), minimal planes of pure color (Ellsworth Kelly); tex- tural elements or subtle variations of line and color (Robert Ryman); a visual display without reference to a separate physical entity (Op Art) or a physical entity devoid of context (Carl Andre) and so forth. Of course, there are abstract pieces that cross the line and do represent a physical entity such as the work of Milton Avery. They are abstract in the sense that they extract some feature or features of their subject without including the detail that would be found in, say, a photograph. I would include these in the realm of representational art.

The purpose of all of this creating images and objects, whether representational or abstract, is to stop time. This is not news to any of us. We all want to mesmerize the viewer, to get it to abandon its life for a while and be enthralled by our work. And, not surprisingly, the viewer wants this, too. People seek art that will provoke or enchant or otherwise blow their mind. They are seeking a thrill. An “Eyegasm,” if you will.

When the viewer relates the artist’s work to his or her own experience there is resonance. This is my favorite metaphor for describing a successful piece of art because the physical analogy is so perfect. If you have two strings of the same mass strung at the same tension, plucking one will cause the other to vibrate. The artist plumbs the depth of its experience to create a work and the viewer is moved. This is the essence of communication. And communication will be the means to solving all of our problems. Artists will save the world.

Time Out

So how will these musings about time inspire specific work? It is certainly not a new subject for artists and it has been approached in many ways. In a chapter on time-related work in Art Since1989, Kelly Grovier wrote “Every work of art is a timepiece - a carefully engineered gizmo that helps us measure the distance of life traversed since its initial windings of our imaginations.” He goes on to describe work by artists who address Time quite literally such as On Kawara who painted the date every day for years; Christian Marclay whose film, The Clock, extracts the image of a clock from a multitude of movies that shows each minute of a day in real time; to artists that take a more metaphorical approach such as Ged Quinn whose painting, The Fall, is an appropriation of a seventeenth century landscape painting infused with additional anachronistic imagery.

In 2006 the Museum of Modern Art in New York presented Out of Time: A Contemporary View, curated by Joachim Pissarro. It included works by Andy Warhol, Rineke Dijkstra, Janine Antoni, and many others that explored various facets of time and our relationship to it in a variety of media. Warhol was represented by an excerpt from Empire (1964), an eight hour static view of the Empire State Building in which only the light changes as the day progresses. Janine Antoni’s Butterfly Kisses (1996-1999) illustrated time’s impact on the creative process. In this piece, she applied mascara to her eyelashes and battered them against paper many times per day over a period of months until the image was completed. Jane and Louise Wilson produced a video installation Stasi City (1997) showing the inside of the abandoned headquarters of the East German secret police. This work is a realization of a memory from a past time, before the fall of the Berlin Wall. Rineke Dijkstra photographed a Bosnian girl whose family had relocated to Amsterdam at eighteen month intervals over a period of eleven years, a time-lapse recording of her development and maturation. These are a few example of the fifty- odd pieces in the show.

When I think about time, I consider both the larger course of history and our biological evolution, as well as the relatively microscopic elements of the moments that we live. In my work, I’m exploring narrative events depicted in serial images or single images with juxtaposed elements that indicate the passage of time. These events may have occurred over a relatively long period of time or in an instant. I’ve long been fascinated by the photographs of Eaweard Muybridge that slowed motion so that the intricacies of movement might be examined in detail.

I also look at “waiting,” a way we all spend much of our time, though there might be a minimum of motion. I want to reveal subtleties to actions and activities that we take for granted but, should perhaps observe more intently. We should ask, “What is this person thinking and feeling as these moments progress?” Each piece will be an experiment that will attempt to stop time in its tracks.

Following are some pieces that were shown at my thesis presentation:

Tali for a Second, Oil on Canvas, 66 x 28”, 2019

Rise & Shine, Oil on canvas, 48x36”, 2019-2021

A Visit to Lydia (tetraptych), Oil on canvas, 44x14”

Dawn (triptych) Lithograph, 36 x 11”, 2019

Pilobolus Dancers, Watercolor on paper, 24 x 18”, 2019. Drawn while danced.

References

Diamond, J.M. (2005) Guns, Germs, and Steel. New York, NY: W.W. Norton& Co.

Doyle, A.C. (1982) The Adventures of Sherlock

Holmes. London in The Strand Grovier, K. (2015) Art Since 1989. noon: Thames & Hudson Ltd.

Harari, Y.N. (2015) SapiensI. New York, NY: Bantam Books

Orwell, G. (1949) Nineteen Eighty-Four. London: Secker & Warburg

Museum of Modern Art press office, (2006) https://www.moma.org/docu- ments/moma_press-release_387109.pdf